Kabbalah , literally “parallel/corresponding,” or “received tradition” is an esoteric method, discipline, and school of thought that originated in Judaism. A traditional Kabbalist in Judaism is called a Mekubal .

Kabbalah’s definition varies according to the tradition and aims of those following it, from its religious origin as an integral part of Judaism, to its later Christian Kabbalah, Hermetic Qabalah and New Age adaptations. Kabbalah is a set of esoteric teachings meant to explain the relationship between an unchanging, eternal, and mysterious Ein Sof (infinity) and the mortal and finite universe (God’s creation). While it is heavily used by some denominations, it is not a religious denomination in itself. It forms the foundations of mystical religious interpretation.

Kabbalah originally developed within the realm of Jewish tradition, and kabbalists often use classical Jewish sources to explain and demonstrate its esoteric teachings. These teachings are held by followers in Judaism to define the inner meaning of both the Hebrew Bible and traditional rabbinic literature and their formerly concealed transmitted dimension, as well as to explain the significance of Jewish religious observances.

Traditional practitioners believe its earliest origins pre-date world religions, forming the primordial blueprint for Creation’s philosophies, religions, sciences, arts, and political systems. Historically, Kabbalah emerged, after earlier forms of Jewish mysticism, in 12th- to 13th-century Southern France and Spain, becoming reinterpreted in the Jewish mystical renaissance of 16th-century Ottoman Palestine. Isaac Luria is considered the father of contemporary Kabbalah. It was popularised in the form of Hasidic Judaism from the 18th century onwards. Twentieth-century interest in Kabbalah has inspired cross-denominational Jewish renewal and contributed to wider non-Jewish contemporary spirituality, as well as engaging its flourishing emergence and historical re-emphasis through newly established academic investigation.

Traditions

According to the Zohar, a foundational text for kabbalistic thought, Torah study can proceed along four levels of interpretation (exegesis). These four levels are called pardes from their initial letters

- Peshat : the direct interpretations of meaning.

- Remez : the allegoric meanings (through allusion).

- Derash : midrashic (rabbinic) meanings, often with imaginative comparisons with similar words or verses.

- Sod : the inner, esoteric (metaphysical) meanings, expressed in kabbalah.

Kabbalah is considered by its followers as a necessary part of the study of Torah – the study of Torah (the Tanakh and rabbinic literature) being an inherent duty of observant Jews.

Modern academic-historical study of Jewish mysticism reserves the term “kabbalah” to designate the particular, distinctive doctrines that textually emerged fully expressed in the Middle Ages, as distinct from the earlier Merkabah mystical concepts and methods. According to this descriptive categorisation, both versions of Kabbalistic theory, the medieval-Zoharic and the early-modern Lurianic kabbalah together comprise the theosophical tradition in Kabbalah, while the meditative-ecstatic Kabbalah incorporates a parallel inter-related Medieval tradition. A third tradition, related but more shunned, involves the magical aims of Practical Kabbalah. Moshe Idel, for example, writes that these 3 basic models can be discerned operating and competing throughout the whole history of Jewish mysticism, beyond the particular Kabbalistic background of the Middle Ages. They can be readily distinguished by their basic intent with respect to God:

- The theosophical tradition of Theoretical Kabbalah (the main focus of the Zohar and Luria) seeks to understand and describe the divine realm. As an alternative to rationalist Jewish philosophy, particularly Maimonides’ Aristotelianism, this speculation became the central component of Kabbalah

- The Ecstatic tradition of Meditative Kabbalah (exemplified by Abulafia and Isaac of Acre) strives to achieve a mystical union with God. Abraham Abulafia’s “Prophetic Kabbalah” was the supreme example of this, though marginal in Kabbalistic development, and his alternative to the program of theosophical Kabbalah

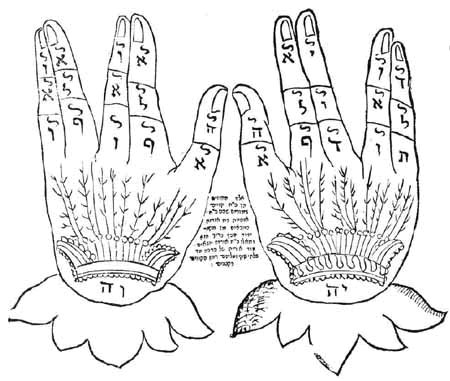

- The Magico-theurgical tradition of Practical Kabbalah (in often unpublished manuscripts) endeavours to alter both the Divine realms and the World. While some interpretations of prayer see its role as manipulating heavenly forces, Practical Kabbalah properly involved white-magical acts, and was censored by kabbalists for only those completely pure of intent. Consequently, it formed a separate minor tradition shunned from Kabbalah. Practical Kabbalah was prohibited by the Arizal until the Temple in Jerusalem is rebuilt and the required state of ritual purity is attainable.

According to traditional belief, early kabbalistic knowledge was transmitted orally by the Patriarchs, prophets, and sages (hakhamim in Hebrew), eventually to be “interwoven” into Jewish religious writings and culture. According to this view, early kabbalah was, in around the 10th century BCE, an open knowledge practiced by over a million people in ancient Israel. Foreign conquests drove the Jewish spiritual leadership of the time (the Sanhedrin) to hide the knowledge and make it secret, fearing that it might be misused if it fell into the wrong hands.

It is hard to clarify with any degree of certainty the exact concepts within kabbalah. There are several different schools of thought with very different outlooks; however, all are accepted as correct. Modern halakhic authorities have tried to narrow the scope and diversity within kabbalah, by restricting study to certain texts, notably Zohar and the teachings of Isaac Luria as passed down through Hayyim ben Joseph Vital. However, even this qualification does little to limit the scope of understanding and expression, as included in those works are commentaries on Abulafian writings, Sefer Yetzirah, Albotonian writings, and the Berit Menuhah, which is known to the kabbalistic elect and which, as described more recently by Gershom Scholem, combined ecstatic with theosophical mysticism. It is therefore important to bear in mind when discussing things such as the sephirot and their interactions that one is dealing with highly abstract concepts that at best can only be understood intuitively.

Jewish and non-Jewish Kabbalah

.

From the Renaissance onwards Jewish Kabbalah texts entered non-Jewish culture, where they were studied and translated by Christian Hebraists and Hermetic occultists. The syncretic traditions of Christian Kabbalah and Hermetic Qabalah developed independently of Jewish Kabbalah, reading the Jewish texts as universal ancient wisdom. Both adapted the Jewish concepts freely from their Judaic understanding, to merge with other theologies, religious traditions and magical associations. With the decline of Christian Cabala in the Age of Reason, Hermetic Qabalah continued as a central underground tradition in Western esotericism. Through these non-Jewish associations with magic, alchemy and divination, Kabbalah acquired some popular occult connotations forbidden within Judaism, where Jewish theurgic Practical Kabbalah was a minor, permitted tradition restricted for a few elite. Today, many publications on Kabbalah belong to the non-Jewish New Age and occult traditions of Cabala, rather than giving an accurate picture of Judaic Kabbalah. Instead, academic and traditional publications now translate and study Judaic Kabbalah for wide readership.

History of Jewish mysticism

Origins

According to the traditional understanding, Kabbalah dates from Eden. It came down from a remote past as a revelation to elect Tzadikim (righteous people), and, for the most part, was preserved only by a privileged few. Talmudic Judaism records its view of the proper protocol for teaching this wisdom, as well as many of its concepts, in the Talmud, Tractate Hagigah, 11b-13a, “One should not teach … the Act of Creation in pairs, nor the Act of the Chariot to an individual, unless he is wise and can understand the implications himself etc.”

Contemporary scholarship suggests that various schools of Jewish esotericism arose at different periods of Jewish history, each reflecting not only prior forms of mysticism, but also the intellectual and cultural milieu of that historical period. Answers to questions of transmission, lineage, influence, and innovation vary greatly and cannot be easily summarised.

Terms

Originally, Kabbalistic knowledge was believed to be an integral part of the Oral Torah, given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai around the 13th century BCE according to its followers; although some believe that Kabbalah began with Adam.

For a few centuries the esoteric knowledge was referred to by its aspect practice—meditation Hitbonenut , Rebbe Nachman of Breslov’s Hitbodedut , translated as “being alone” or “isolating oneself”, or by a different term describing the actual, desired goal of the practice—prophecy .

During the 5th century BCE, when the works of the Tanakh were edited and canonised and the secret knowledge encrypted within the various writings and scrolls (“Megilot”), the knowledge was referred to as Ma’aseh Merkavah and Ma’aseh B’reshit respectively “the act of the Chariot” and “the act of Creation”.

Merkabah mysticism alluded to the encrypted knowledge within the book of the prophet Ezekiel describing his vision of the “Divine Chariot”. B’reshit mysticism referred to the first chapter of Genesis in the Torah that is believed to contain secrets of the creation of the universe and forces of nature. These terms are also mentioned in the second chapter of the Talmudic tractate Hagigah .